“I’m very happy to announce that after almost 40 years of litigation against Sugarhill records, we settled out of court after an independent arbitrator determined the amount owed and we were awarded back royalties and moving forward all of our writers & publishing will come directly to us! Victory as of TODAY!!!!!”

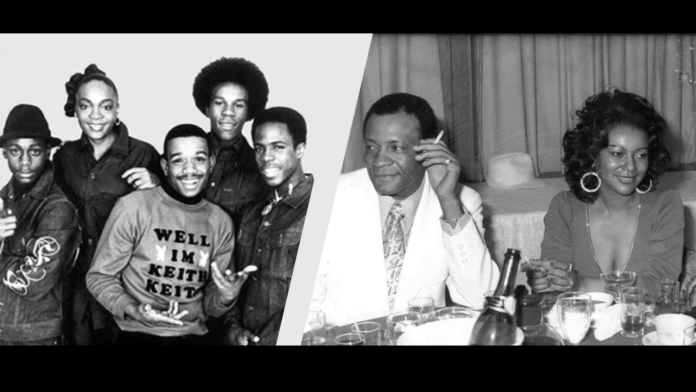

This message was released by the emcee Rahiem who was a member of the Funky Four Plus One and would later go on to join Grandmaster Flash and The Furious Five. Rahiem’s celebration along with the members of both of his groups as well as other artists that had been signed to Sugar Hill Records, is something of a landmark. In the long music industry history of exploitation, protest, and litigation, artists suing their record labels is nothing new. A group of artists winning their lawsuit after nearly four decades is more of a novel concept and the players in those 40ish years of court cases have a deep place in the story of Hip Hop.

Sugar Hill Records was founded by husband and wife, Sylvia and Joe Robinson in 1979. They built the label from the ashes of All Platinum Records, a bankrupted label they had previously founded and lost, leaving the pair scrambling to find something to bring them back on top. The story goes that a chance night at the club Harlem World on the corner of Lenox and 116th Street in New York, brought Sylvia into the presence of Hip Hop. After watching Lovebug Starski rap over an instrumental break of Good Times by Chic, she realized that she was witnessing something that would change the world and resolved herself to be at the forefront of the commercialization of rap. Wasting no time, she set to work assembling a trio of would-be rappers, pulling one of them right out of his job at a pizza joint, and built a song called “Rapper’s Delight” that would live in infamy, Hip Hop’s first hit song also to be considered by many to be a Frankenstein-like recreation of the culture that had inspired Sylvia that night in Harlem. She would name the group of rappers she assembled from New Jersey, and the record label their song had spawned Sugar Hill, after the upscale Harlem neighborhood which had overlooked her home growing up on 137th Street, the hill that Langston Hughes, writing for the Republic in 1944, would describe as “that attractive rise of bluff and parkway… where the plumbing really works and the ceilings are high and airy.”

A group of guys from New Jersey named after a neighborhood in New York may be an odd enough contradiction to be an apropos symbol of what Sylvia and Joe were creating. To say that Sugar Hill Records has a complex lineage in the story of Hip Hop would be an understatement. The lawsuit that was just settled between the Funky 4 Plus One, Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five, and Sugar Hill Records after 40 years of litigation is one of many in a long line of lawsuits and trials. Sugar Hill’s long legal history is riddled with missing writer’s credits, accusations of unpaid royalties, and even tax evasion- a federal case in which the three children of Silvia and Joe Robinson plead guilty after their parents had already turned control of the label over to them.

Musically, Rapper’s Delight is often criticized for, among other things, misunderstanding the nature of the culture at the time and spotlighting the emcees while demoting the DJ to a background figure. In response to the criticism, Sugar Hill records would release The Adventures of Grandmaster Flash on the Wheels of Steel, a song that would shine a new spotlight on the artform of the DJ in Hip Hop and would lay the groundwork for the loop driven music of the culture’s musical golden age. Sylvia is credited with co-producing The Message by Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five, one of early Hip Hop’s most powerful works, showing that a strong social message and commercial success weren’t mutually exclusive. But commercial success doesn’t always mean financial success for everyone.

Most Hip Hop heads will know that Q-Tip laid out a caveat for artists in the music business on A Tribe Called Quest’s, Check the Rhime: “Industry rule #4080, record company people are shady.” In an interview on Vlad TV, Melle Mel, when asked if he’d filed a lawsuit against Sugar Hill records for stolen profits on his music said, “All the groups that were signed to Sugar Hill filed a lawsuit.” Sha Rock, member of the Funky Four Plus One and by many historian accounts, the first known female emcee, posted a notice on her Facebook after the recent settlement with Sugar Hill briefly describing the story of the decades long lawsuit:

“We’ve finally won against Sugar Hill Records. Let me give you the back story. Back in the early 90’s after returning to the United States from Germany, I worked effortlessly on finding an attorney to take on Sugar Hill Records. No one wanted to take my case. I eventually came across a woman who put me in touch with Artist Rights Enforcement in New York City, who fights for artist rights. I became their first hip hop client. I brought in the Funky 4+1 and then went to Rahiem to bring in the Furious 5. I also tried to include the Sequence… to file a class action lawsuit, but they didn’t want any part of the lawsuit. 1979… I recorded my first rap record under Enjoy Records. June 1980, the Funky 4 signed to Sugar Hill Records. We’ve been back [and] forth to court since the 1990’s. We’ve won all of our cases. 42 years later, I as well as the Funky 4+1 More, The Furious 5, and Reggie Payne from the Crash Crew have been vindicated.”

The plaintiffs in this case are celebrating a long and hard fought victory over their record label but history will tell that these victories are few and far between. Even the most powerful artists in the recording industry have had limited success when pursuing equity from their labels. Prince’s battle with Warner Brothers, for example, lasted years and when he was finally able to sever ties with the label, he’d paid a hefty price in legal fees and contract sacrifices. The press release he put out after the severance mirrored Q-Tip’s timeless warning, “My ultimate message,” Prince wrote, “is a cry for solidarity amongst artists and a reprieve from the greed of entertainment executives.”

Musicians having to fight for their fair share is often regarded as an industry standard and artists with less leverage than Prince have a harder fight ahead of them with far less chance of success. Going back to Rapper’s Delight, Chic’s Nile Rodgers and Bernard Edwards had to take the Robinsons to court to get their royalties for composing the music that was replayed by a house band on the song. Other artists associated with the song never got paid for their work. When Curtis Fisher also known as Grandmaster Caz, famously tossed his rhyme book to Hank Lee Jackson, the pizza parlor employee soon to become platinum rapper Big Bank Hank, he had no idea that his lyrics would appear on the first rap song to top Billboard’s R&B tally and sell over a million records. Sylvia Robinson is credited on Rapper’s Delight as a songwriter but as of the date of this article’s writing, Grandmaster Caz is still not.

In the years since Rapper’s Delight took the summer of ‘79 by storm, controversy has stirred around the record label that produced it. That controversy didn’t begin with Sugar Hill Records and it didn’t end when Sylvia, Joe, and their son and label partner Joey Jr. passed on from medical conditions. Other family members and stakeholders behind Sugar Hill Records absorbed its legacy, diluting its interests back into the industry well it sprung from four decades ago. Industry rule #4080 is the reminder of the cold reality that the artists who write the words and melodies that become songs that draw laughter, tears, and booty shaking out of listeners, live and work within a system that doesn’t regard them as equals. Money talks and in the entertainment industry, “it’s all in the contract” has always been a popular phrase.

MC Sha Rock’s Facebook post about her settlement concluded with a telling statement:

“We won our final judgment. People [used] to think I was tripping, simply because I’ve always spoken on the lawsuit and was determined to see this through. Some said let it go. I can’t discuss the amount, but it’s finally over. Or [we’ll] be back in court if my money is short.”

In the relationship between workers and corporations, musicians and record labels, players and owners, there is a power dynamic at play. Many of the workers, musicians, and players feel that dynamic is akin to predator and prey. In nature, that relationship fuels evolution. As the hunter wields its power, the object of its hunt develops new ways of surviving and in turn becomes stronger. Well financed corporations hold a great deal of power but with each victory like the one The Funky Four Plus One, Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five, and Reggie Payne are celebrating, it brings to mind that power doesn’t live only in one place. As musicians continue to work towards fairness within their label deals and lead the struggle on into the new mediums of streaming and digital downloads, the fight continues. Musician support organizations like Artists Rights Enforcement Corporation, Artist Rights Alliance, and others are growing in numbers and savvy. New tools for fair pay advocacy in music are continuing to evolve and from Sha Rock’s perspective, a great victory was just won on the artists’ behalf. But that doesn’t mean she’s ready to rest because if that money is short, they’ll be back in court.