A recent study published by researchers in the Department of Neurosurgery at Copenhagen University Hospital in Denmark, takes a new look at the effects of breaking on the human body. To consider the bigger picture of what studies like this mean about Hip Hop’s place in the modern world, a step back may be useful.

The introduction of the Hip Hop element of breaking as an official sport in the 2024 Olympic Games in Paris has prompted a wide variety of conversations around the world. While much of popular media’s attention has been focused on the spectacle of the events, posting and reposting endless memes of b-girl Raygun’s kangaroo hops and toe touches, conversations from within Hip Hop have often leaned deeper into investigating the greater implications of mass appeal on the state of the culture. As Hip Hop ages and awareness of its elements grows, the larger impact of its existence on the global landscape can be observed in entirely new ways.

Hip Hop has come to a point in its 50 year lifespan where it has become obvious that the marks it has left on the history of humanity are extending beyond influencing artistic movements, shifting fashion trends, and filling the world with freshly minted slang. Hip Hop, in its innocuity, has shown an ability to move markets, unify international language groups, and similar to Jazz before it, to break into many of our society’s exclusive institutions as evidenced with instances like Kendrick Lamar being awarded a 2018 Pulitzer prize for his album DAMN. Most recently, Hip Hop’s impact is being seen through new interactions with science and medicine.

In the October 2024 Copenhagen University Hospital case report1, the study’s authors detail the medical case of an unnamed b-boy suffering from what the researchers term, a ‘headspin hole.’ As documented in the report’s abstract, a headspin hole is “a unique overuse injury in breakdancers caused by repetitive headspins. It manifests as a fibrous mass on the scalp, hair loss and tenderness.” Many Hip Hop practitioners with close relationships to breakers, are familiar with the small lump that sometimes develops in the center of the head of active dancers but the Danish study on the subject raises some points that open up a broader context when considering the phenomenon.

In regards to the medical hazards of repetitive headspins, this is nothing new within Hip Hop. Speaking to the NY Post in response to the recent study, former New York City Breakers member Tony “Mr. Wave” Wesley states that the condition of forming a lump on the top of the head is a result of “wrong mechanics of going down on the floor with too much force. It’s the pounding, not the spinning… It’s no different than lifting weights. If you don’t have proper technique, you’re going to hurt yourself.” Aside from technique, many breakers use beanies with patches in the center, helmets, and other protective devices to protect their heads while bearing the weight of headspins.

Mr. Wave also notes another implication of the ‘headspin lump.’ Of those who practice an element in Hip Hop, there are many who live by the maxim, “each one, teach one.” Teaching artists are a standard within the culture and as Mr. Wave notes, a veteran breaker would tell younger breakers to “lower themselves onto the ground in a slower, handstand-style instead of diving dome-first.”

Speaking about younger dancers who haven’t received that training, he reflects on some of the ways that technology has affected the way we learn, leading many from younger generations to gain knowledge from the internet rather than directly from older mentors in the craft. As a result, “Now these kids go straight into the power moves,” Mr. Wave says. “It’s riskier what they do today, [but with proper knowledge] it’s as safe as you want it to be.”

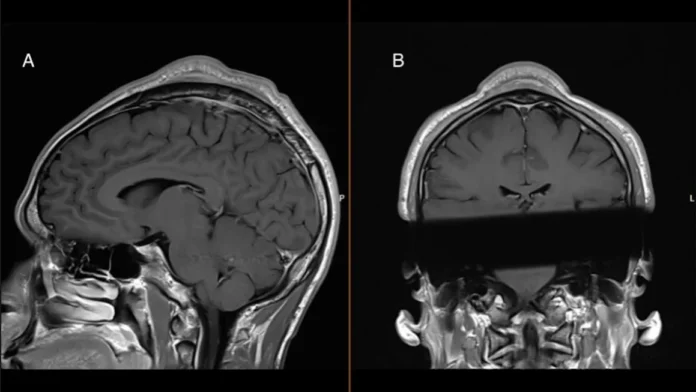

The anonymous male breaker in the recent Danish study was in his early-30’s and reported to have developed the protuberance in his scalp over the span of 5 years of extensive practice head-spinning. After identifying the growth as fibrosis, the scarring of connective tissue in the human body, and a thickening of the subcutis, our deepest layer of skin, the dancer underwent a surgical removal of the mass and shaving of the excess surface tissue. The surgery proved successful in relieving symptoms of the condition as well as a notable aesthetic improvement. This means that in studying this phenomenon unique to Hip Hop, a fresh medical precedent has been established as the report concludes, “This case underscores the importance of recognizing chronic scalp conditions in breakdancers and suggests that surgical intervention can be an effective treatment.”

BMJ Case Reports 2024

While studies like this are in fact limited, they’re also not entirely new. For example, a 2023 German study2 investigated the relationship between breaking and the development of alopecia, a condition which occurs when hair follicles are damaged due to repeated tugging at their roots.

The study which surveyed 106 breakers, identified that around 60% reported head-related overuse injuries, with 31% experiencing hair loss and 24% developing painless bumps on their heads. It’s worth noting that other variables, such as age, gender, drug and alcohol use were taken into consideration, but the rate of hair loss indicated in the study, regarding breakers, was quite stark. When compared to dancers practicing in other styles, the report reads, “There was a significant difference in balding between breaking and other types of dancing. While 45.07% of breakers reported balding, only 23.94% of other dancers reported hair loss. Logistic regression showed that breakers were 2.6 times more likely to report balding than non-breakers.”

While this data is informative and certainly speaks to the necessity of proper technique and protective gear for dancers, the report also looked at the results in the inverse, considering how premature balding might affect the psyche of the dancers. While not proposing that their data provided an answer to any specific question in regards to mental health, the inquiry did extend to considering how the psychological state of the breaker might impact their performance. This means that studies of this type have a continued potential for initiating further research, even between disciplines as different as dermatology and psychology.

Sometimes the effect of breaking on brain function is more physiological in nature, as detailed in a report3 published by Dr. Maxime Maheu in the Journal of Neurophysiology. Dr. Maheu is an assistant professor at the University of Montreal where he studies the inner workings of the vestibular system, the neural system in the brain that helps to govern balance, spatial orientation, and eye movement. Part of the purpose of his research is to help patients with conditions that disrupt their sense of balance. By comparing non-dancers to dancers, especially dancers who often perform moves that include repetitive spinning, he is seeking ways in which specific moves make changes to a dancer’s nervous system, providing data that could inform vestibular rehabilitation programs.

(Photo: Jair Fernando Coll Rubiano, NPR)

Dr. Maheu’s study looked specifically at the vestibulo-ocular reflex (VOR), an involuntary reflex that shifts the eyes in order to stabilize the visual field while the head is moving. The VOR engages when the eyes are focussed on a fixed point while the head turns quickly. It is suppressed when a moving object is being tracked. The study, initially using ballet dancers as subjects, found that compared to non-dancers, the dancers’ eyes moved “slightly faster than the head did for the first millisecond it was moving.”

Furthermore, research garnered from moves unique to dance styles like breaking have far greater potential impacts on the field of medicine. In a 2018 study4 by Dr. Maheu compared results between 12 non-dancers and 12 dancers of various styles with repetitive spinning techniques including breaking. The subjects were asked to track a moving object while simultaneously moving their own head. “They [the dancers] did not completely switch off the VOR but were able to move their eyes earlier to correct [their focus],” Maheu said of the results. This result increased with the amount of training and years of experience dancers had amassed previous to the study.

In breaking, as in ballet, gymnastics, and other high level athletic arts, performers practice a series of movements over and over, slowly increasing the complexity of the sequence in order to build muscle memory. Studies suggest that, over time, such complicated series of movements become locked into one highly efficient explosion of brain activity. This method of the brain explains the improvisational nature of breaking and other Hip Hop art forms such as a freestyling emcee, in which the artist finds ‘the pocket’ where they no longer have to think about the minutiae of their performance, but rather react to a subconscious relationship between their mind and body.

While more research is needed to prove the premise, the idea is that training in dance, such as breaking, can create changes in the vestibular system of the human brain. Dr. Maheu concludes, “We don’t know for sure how dance training may explain this result, but it could offer interesting new paths to follow for vestibular rehabilitation.”

It may not have been on the minds of the Mighty Zulu Kings, the Dynamic Rockers, or the Rocksteady Crew when they were developing the art of breaking in the 1970’s but decades later, it’s a powerful footnote in Hip Hop’s history to consider that further studies of the art form those pioneers created could offer data that can potentially be used in developing healing pathways for people with a wide range of conditions that impact balance from simple vertigo to diabetes and thyroid disorders.

The level of spectacle that Hip Hop is capable of producing will continue to create sensational moments and make news. Some of the headlines will be about Super Bowl performers and court cases. Some will be jokes about a questionable performance in a global competition. Within those headlines, people inside the culture will continue to debate the impact of aligning with the infrastructures that create the spectacles of Super Bowls and Olympic Games. People will discuss the mental health of the individuals being ridiculed in the joke headlines and continue to think and rethink the myriad ways that Hip Hop’s practitioners impact its trajectory. From all that, new art will emerge, and while that art will most definitely make people move and dance, it will also provide examples that might just teach humans to heal themselves in new ways. That’s good medicine.

Citations:

1Skotting MB, Søndergaard CB‘Headspin hole’: an overuse injury among breakdancersBMJ Case Reports CP 2024;17:e261854. (Link)

2Hall M, Lim H, Kim S, Fulda KG, Surve SA. A Cross-Sectional Study Comparing Traumatic Alopecia Among B-Boys and B-Girls to Other Dance Styles and Its Impact on Dance Performance and Health. Journal of Dance Medicine & Science. 2023;27(1):13-19. doi:10.1177/1089313X231176598 (Link)

3Long-term dance training modifies eye-head coordination in response to passive head impulse Karina Moin-Darbari, Mujda Nooristani, Benoit-Antoine Bacon, François Champoux, and Maxime Maheu. Journal of Neurophysiology 2023 130:4, 999-1007 (Link)

4Maheu, M., Behtani, L., Nooristani, M. et al. Enhanced vestibulo-ocular reflex suppression in dancers during passive high-velocity head impulses. Exp Brain Res 237, 411–416 (2019). ((Link)